|

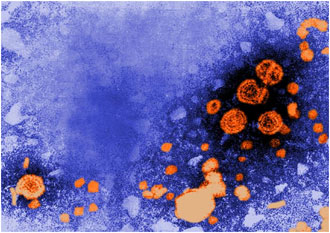

This transmission electron

micrograph (TEM) revealed the presence of hepatitis B virions.

The large round virions are known as Dane particles.

Photo courtesy of CDC/ Dr. Erskine Palmer.

This transmission electron

micrograph (TEM) revealed the presence of hepatitis B virions.

The large round virions are known as Dane particles.

Photo courtesy of CDC/ Dr. Erskine Palmer. High Risk Exposures

The healthcare setting can be a risky place

to work. During the provision of routine healthcare, there

exist high risk practices and procedures that are capable

of causing healthcare acquired infection with blood borne

pathogens.

More than 8 million U.S. healthcare workers

in hospitals may be exposed to blood or other body fluids

through the following types of contact (NIOSH, 2004):

- Percutaneous injuries (injuries through the skin) with

contaminated sharp instruments such as needles and scalpels

(82%)

- Contact with mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, or mouth

(14%)

- Exposure of broken or abraded skin (3%)

- Human bites (1%)

The revised New York State syllabus for the

Mandatory Infection Control training identifies high risk

practices and procedures capable of causing healthcare acquired

infection with bloodborne pathogens:

- Percutaneous exposures

- Other sharps injuries

- Mucous membranes and non-intact skin exposures

- Parenteral exposure.

Percutaneous exposures occur through handling/disassembly/disposal/reprocessing

of contaminated needles and other sharp objects. This can

occur through manipulating contaminated needles and other

sharp objects by hand (e.g., removing scalpel blades from

holders, removing needles from syringes, or recapping contaminated

needles and other sharp objects using a two-handed technique),

or by delaying or improperly disposing (e.g., leaving contaminated

needles or sharp objects on counters/workspaces or disposing

in non-puncture-resistant receptacles) (NYSDOH, 2008; NIOSH,

2004).

Up to 800,000 percutaneous injuries may occur annually among

all U.S. healthcare workers (both hospital-based workers and

those in other health care settings). After percutaneous injury

with a contaminated sharp instrument, the average risk of

infection is 0.3% for HIV and ranges from 6% to 30% for HBV

(NIOSH, 2004). On a positive note, the CDC has reported no

new cases of occupationally-acquired HIV since 2001 (CDC,

2006).

During the period 1995-2000, there were 10,378 reported percutaneous

injuries among hospital workers (NIOSH, 2004). The devices

most associated with percutaneous injuries among hospital

workers during 1995-2000 were hypodermic needles (29% of injuries),

suture needles (17%), winged steel needles (12%), and scalpels

(7%). Other hollow-bore needles together accounted for 19%

of injuries, glass items for 2%, and other items for 14% (NIOSH,

2004).

During the period 1995-2000 there were 6,212 reported percutaneous

injuries involving hollow-bore needles in hospital workers.

Drawing blood from a vein (venipuncture) was responsible for

25% of percutaneous injuries involving hollow-bore needles

during 1995-2000, and injections were responsible for 22%

(NIOSH, 2004).

Recent research on a nationally representative sample utilizing

data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, identified registered

nurses as having the greatest frequency of needlestick injury

(Leigh, et al., 2008); while the occupations with greatest

risk of needlestick injury included biologic technicians,

janitors and cleaners, and maids and housemen.

Other means of sharps injury can occur when performing

procedures where there is poor visualization, such as: Blind

suturing, non-dominant hand opposing or next to a sharp, or

performing procedures where bone spicules or metal fragments

are produced.

Mucous membranes and non-intact skin exposures are

also a potential method for exposure to bloodborne pathogens.

Direct blood or body fluid contact with the eyes, nose, mouth

or other mucous membranes occurs through contact with contaminated

hands, contact with open skin lesions/dermatitis, or splashes/sprays

of blood or body fluids such as might occur during irrigation

or suctioning.

Parenteral exposures may occur through injection with

infectious material while administering parenteral medications,

sharing of blood monitoring devices such as glucometers, hemoglobinometers,

lancets, lancet platforms/pens, or through the infusion of

contaminated blood products or fluids.

Additional practice to prevent percutaneous exposures include:

- Avoid unnecessary use of needles and other sharp objects.

- Use care in the handling and disposing of needles and

other sharp objects.

- Avoid recapping unless absolutely medically necessary.

- When recapping, use only a one-hand technique or safety

device.

- Pass sharp instruments by use of designated "safe zones".

- A "safe zone" is an area such as a tray or basin

on the sterile field where an instrument is placed before

being picked up by a second person. This can prevent

"collision" injuries where OR personnel can be tuck

by another when passing instruments.

- Disassemble sharp equipment by use of forceps or other

devices.

- Modify procedures to avoid injury:

- Use forceps, suture holders or other instruments

for suturing.

- Avoid holding tissue with fingers when suturing or

cutting.

- Avoid leaving exposed sharps of any kind on patient

procedure/treatment work surfaces.

- Appropriately use safety devices whenever available:

- Always activate safety features. o Never circumvent

safety features.

Safe Injection Practices and Procedures

Outbreaks of healthcare-related bloodborne illness have occurred,

usually due to unsafe injection practices. Recent news headlines

that implicate specific healthcare organizations and specific

healthcare providers for unsafe injection practices shocked

the thousands of patients who may have had exposure to bloodborne

pathogens, but such practices and procedures also shocked

the broader healthcare community.

Injection safety or safe injection practices are a

set of measures taken to perform injections in an optimally

safe manner for patients, healthcare personnel, and others.

A safe injection does not harm the recipient, does not expose

the provider to any avoidable risks and does not result in

waste that is dangerous for the community. Injection safety

includes practices intended to prevent transmission of bloodborne

pathogens between one patient and another, or between a healthcare

worker and a patient, and also to prevent harms such as needlestick

injuries.

The investigation of four large outbreaks of HBV and HCV

among patients in ambulatory care facilities in the United

States identified a need to define and reinforce safe injection

practices (CDC, 2008b). The four outbreaks occurred in a private

medical practice, a pain clinic, an endoscopy clinic, and

a hematology/oncology clinic. The pain clinic was located

on Long Island, New York. The primary breaches in infection

control practice that contributed to these outbreaks were:

- reinsertion of used needles into a multiple-dose vial

or solution container (e.g., saline bag) and

- use of a single needle/syringe to administer intravenous

medication to multiple patients.

In one of these outbreaks, preparation of medications in

the same workspace where used needle/syringes were dismantled

also may have been a contributing factor. These and other

outbreaks of viral hepatitis could have been prevented by

adherence to basic principles of aseptic technique for the

preparation and administration of parenteral medications.

These include the use of a sterile, single-use, disposable

needle and syringe for each injection given and prevention

of contamination of injection equipment and medication.

The unsafe practices above have resulted in the transmission

of bloodborne viruses, including hepatitis B and C viruses

to patients; as well as the notification of thousands of patients

of possible exposure to bloodborne pathogens and recommendation

that they be tested for hepatitis C, hepatitis B virus, and

HIV. Additionally, healthcare providers were referred to licensing

boards for disciplinary action and multiple malpractice lawsuits

were filed on behalf of patients.

Outbreaks related to unsafe injection practices indicate

that some healthcare personnel are unaware of, do not understand,

or do not adhere to basic principles of infection control

and aseptic technique. A survey of US healthcare workers who

provide medication through injection found that 1% to 3% reused

the same needle and/or syringe on multiple patients. Among

the deficiencies identified in recent outbreaks were a lack

of oversight of personnel and failure to follow-up on reported

breaches in infection control practices in ambulatory settings

(CDC, 2008b).

It is important for to remember that pathogens including

HCV, HBV, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be present

in sufficient quantities to produce infection in the absence

of visible blood. Bacteria and other microbes can be present

without clouding or other visible evidence of contamination.

The absence of visible blood or signs of contamination in

a used syringe, IV tubing, multi-dose medication vial, or

blood glucose monitoring device does NOT mean the item is

free from potentially infectious agents.

All used injection supplies and materials are potentially

contaminated and should be discarded.

Providers should maintain aseptic technique throughout

all aspects of injection preparation and administration, which

includes the following:

- Medications should be drawn up in a designated "clean"

medication area that is not adjacent to areas where potentially

contaminated items are placed.

- Use a new sterile syringe and needle to draw up medications

while preventing contact between the injection materials

and the non-sterile environment.

- Ensure proper hand hygiene before handling medications.

- If a medication vial has already been opened, the rubber

septum should be disinfected with alcohol prior to piercing

it.

- Never leave a needle or other device (e.g. "spikes")

inserted into a medication vial septum or IV bag/bottle

for multiple uses. This provides a direct route for microorganisms

to enter the vial and contaminate the fluid.

- Medication vials should be discarded upon expiration or

any time there are concerns regarding the sterility of the

medication.

- Never administer medications from the same syringe to

more than one patient, even if the needle is changed.

- Never use the same syringe or needle to administer IV

medications to more than one patient, even if the medication

is administered into the IV tubing, regardless of the distance

from the IV insertion site.

- All of the infusion components from the infusate to

the patient's catheter are a single interconnected unit.

- All of the components are directly or indirectly

exposed to the patient's blood and cannot be used for

another patient.

- Syringes and needles that intersect through any port

in the IV system also become contaminated and cannot

be used for another patient or used to re-enter a non-patient

specific multi-dose vial.

- Separation from the patient's IV by distance, gravity

and/or positive infusion pressure does not ensure that

small amounts of blood are not present in these items.

- Never enter a vial with a syringe or needle that has

been used for a patient if the same medication vial might

be used for another patient.

- Dedicate vials of medication to a single patient.

- Medications packaged as single-use must never be used

for more than one patient:

- Never combine leftover contents for later use;

- Medications packaged as multi-use should be assigned

to a single patient whenever possible;

- Never use bags or bottles of intravenous solution

as a common source of supply for more than one patient.

- Never use peripheral capillary blood monitoring devices

packaged as single-patient use on more than one patient:

- Restrict use of peripheral capillary blood sampling devices

to individual patients.

- Never reuse lancets. Consider selecting single-use lancets

that permanently retract upon puncture.

Safe injection practices as identified in the CDC's

Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission

of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings 2007 include

the following recommendations apply to the use of needles,

cannulas that replace needles, and, where applicable intravenous

delivery systems (CDC, 2007):

- Use aseptic technique to avoid contamination of sterile

injection equipment.

- Do not administer medications from a syringe to multiple

patients, even if the needle or cannula on the syringe is

changed. Needles, cannulae and syringes are sterile, single-use

items; they should not be reused for another patient nor

to access a medication or solution that might be used for

a subsequent patient.

- Use fluid infusion and administration sets (i.e., intravenous

bags, tubing and connectors) for one patient only and dispose

appropriately after use. Consider a syringe or needle/cannula

contaminated once it has been used to enter or connect to

a patient's intravenous infusion bag or administration set.

- Use single-dose vials for parenteral medications whenever

possible.

- Do not administer medications from single-dose vials

or ampules to multiple patients or combine leftover contents

for later use.

- If multidose vials must be used, both the needle or cannula

and syringe used to access the multidose vial must be sterile.

- Do not keep multidose vials in the immediate patient

treatment area and store in accordance with the manufacturer's

recommendations; discard if sterility is compromised or

questionable.

- Do not use bags or bottles of intravenous solution as

a common source of supply for multiple patients.

Surveillance/Evaluation

Each year an estimated 385,000 needlesticks and other sharps-related

injuries are sustained by hospital-based healthcare personnel;

an average of 1,000 sharps injuries per day (NIOSH, 2008).

Healthcare providers who may be exposed to blood or other

potentially infected material are at risk, particularly if

they are exposed to contaminated needles or other contaminated

sharps that may cause injury. In addition to the surveillance

needed regarding the potential for injury to healthcare providers,

similarly, surveillance is used to identify factors related

to the 2 million HAIs per year.

Surveillance is defined as the ongoing, systematic collection,

analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of data regarding

a health-related event for use in public health action to

reduce morbidity and mortality and to improve health (CDC,

2007). Multiple agencies require ongoing evaluation of potential

hazards from bloodborne pathogens, including the Occupational

Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institute for Occupational

Safety and Health (NIOSH). In New York State, the Department

of Health and each individual healthcare organization or facility

has policies that support the safety of patients and healthcare

providers, as well as identifying how and to whom HAIs are

reported and analyzed.

A comprehensive standardized method for recording and tracking

percutaneous injuries and blood and body fluid contact is

the Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet). The

EPINet system consists of a Needlestick and Sharp Object Injury

Report and a Blood and Body Fluid Exposure Report, and software

programmed in Access®* for entering and analyzing the data

from the forms. (A post-exposure follow-up form is also available.)

Since its introduction in 1992, more than 1,500 hospitals

in the U.S. have acquired EPINet for use; it has also been

adopted in other countries, including Canada, Italy, Spain,

Japan and U.K (EPINET, 2008). With this system, the following

is available:

- Identify injuries that may be prevented with safer medical

devices.

- Share and compare information and successful prevention

measures with other institutions.

- Evaluate the efficacy of new devices designed to prevent

injuries.

- Target high-risk devices and procedures for intervention.

- Analyze injury frequencies by attributes like jobs, devices,

and procedures.

- Prepare monthly, quarterly, and annual exposure reports.

They can be accessed at http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/epinet/about_epinet.cfm#What-is-EPINet.

While any sharp device can cause injury and has the potential

for disease transmission, some devices have a higher disease

transmission risk, such as hollow-bore needles. Other devices

have higher injury rates, such as butterfly-type IV catheters

and devices with recoil action, blood glucose monitoring devices

with lancet platforms/pens. It is important to identify the

settings in which exposures occur and the circumstances by

which exposure is more likely to occur.

Contiune to Element III,

Con't.

|

|