|

Comprehensive Prevention Model

The CDC’s (nda) Preventing Shaken Baby Syndrome: A Guide for Health Departments and Community-Based Organizations A part of CDC’s “Heads Up” Series, provides a model for the prevention of AHT.

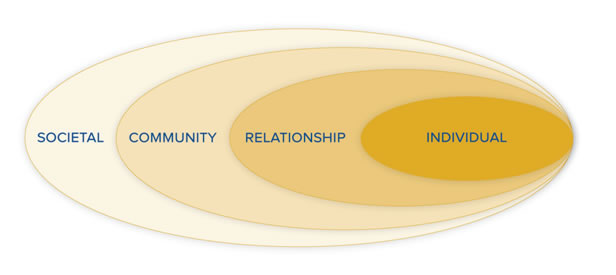

Prevention requires understanding the factors that influence violence. CDC uses a four-level social-ecological model to better understand violence and the effect of potential prevention strategies. This model considers the complex interplay between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors and is more likely to sustain prevention efforts over time than any single intervention.

http://www.cdc.gov/Concussion/pdf/Preventing_SBS_508-a.pdf

Individual level strategies – These are the interventions that are aimed at parents and caretakers of infants and children, and changing their knowledge and skills.

Relationship level strategies – These are interventions that are aimed at trying to change the interactions between people: parents and children, parents and other caregivers, parents and healthcare providers, bystanders and parents.

Community level strategies – These are strategies that are aimed at modifying the characteristics of settings that give rise to violence or that protect against violence

.

Societal level strategies – These are aimed at changing cultural norms surrounding parenting, as well as laws and policies that support parents.

Individual Strategies: Public Health Intervention

Primary prevention public health strategies have been utilized with success in the past with AHT, as well as other conditions, for example HIV/AIDS. Primary prevention programs need to reach a large number of persons; it is important that they be inexpensive and easy to administer. A simple program containing a powerful message, administered at the appropriate moment and requiring very little effort or time on the part of those who deliver the message and those who receive it, has the greatest chance of success (Dias, et al., 2005).

AHT occurs most frequently in response to a crying infant (CDC, nda). Crying—including long bouts of inconsolable crying—is normal developmental behavior in infants. The problem is not the crying, it’s how caregivers respond to it. Picking up a baby and shaking, throwing, hitting, or hurting him or her is never an appropriate response. Everyone, from caregivers to bystanders, can do something to prevent AHT. Giving parents and caregivers tools that can help them cope if they find themselves becoming frustrated while caring for a baby are important components of any AHT prevention program

The National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome (NCSBS) has developed The Period of PURPLE Crying as a public health intervention. The purpose is to educate parents about the normalcy of infant crying and the dangers of shaking an infant.

The acronym PURPLE describe specific characteristics of an infant’s crying during this phase of life and lets parents and caregivers know that what they are experiencing is indeed normal and, although frustrating, is simply a phase in their child’s development that will pass. The word period is important because it tells parents that it is only temporary and will come to and end.

P=Peak of Crying

Your baby may cry more each week; the most at 2 months, then less at 3-5 months.

U=Unexpected

Crying can come and go and you don’t know why.

R=Resists Soothing

Your baby may not stop crying no matter what you try.

P=Pain-like Face

A crying baby may look like she or he is in pain even when they are not.

L=Long Lasting

Crying can last as much as 5 hours per day, or more.

E=Evening

Your baby may cry more in the late afternoon or evening.

For more information on this particular public health strategy, go to http://purplecrying.info/. |

The CDC (nda) offers the following:

Prevention Tips for Parents and Caregivers

- Babies cry a lot in the first few months of life and this can be frustrating, but it will get better.

- Remember, you are not a bad parent or caregiver if your baby continues to cry after you have done all you can to calm him or her.

- You can try to calm your crying baby by:

- Rubbing his or her back,

- Gently rocking,

- offering a pacifier,

- singing or talking, or

- Taking a walk using a stroller or a drive with the baby in a properly-secured car seat.

- If you have tried various ways to calm your baby and he or she won’t stop crying, do the following:

- Check for signs of illness or discomfort like diaper rash, teething, or tight clothing.

- Call the doctor if you suspect your child is ill.

- Assess whether he/she is hungry or needs to be burped.

- If you find yourself pushed to the limit by a crying baby, you may need to focus on calming yourself. Put your baby in a crib on his or her back, make sure he or she is safe, and then walk away for a bit and call a friend, relative, neighbor, or parent helpline for support. Check on him or her every 5 to 10 minutes.

- Tell everyone who cares for your baby about the dangers of shaking a baby and what to do if they become angry, frustrated, or upset when your baby has an episode of inconsolable crying or does other things that caregivers may find annoying, such as interrupting television, video games, sleep time, etc.

- Be aware of signs of frustration and anger among others caring for your baby. let them know that crying is normal and that it will get better.

- Do not leave your baby in the care of someone you know has anger management issues.

- See a health care professional if you have anger management or other behavioral concerns.

- Understand that you may not be able to calm your baby and that it is not your fault, nor your baby’s. It is normal for healthy babies to cry much more in the first 4 months of life.

|

The National Institutes of Health (2009) have the following message:

- NEVER shake a baby or child in play or in anger. Even gentle shaking can become violent shaking when you are angry.

- Do not hold your baby during an argument.

- If you find yourself becoming annoyed or angry with your baby, put him in the crib and leave the room. Try to calm down. Call someone for support.

- Call a friend or relative to come and stay with the child if you feel out of control.

- Contact a local crisis hotline or child abuse hotline for help and guidance.

- Seek the help of a counselor and attend parenting classes.

- Do not ignore the signs if you suspect child abuse in your home or in the home of someone you know.

|

The American Association of Pediatrics (2010) message:

If you feel as if you might lose control when caring for your baby:

- Take a deep breath and count to ten.

- Put your baby in her crib or another safe place, leave the room, and let her cry alone.

- Call a friend or relative for emotional support.

- Give your pediatrician a call. Perhaps there’s a medical reason why your baby is crying.

|

The CDC (nda) offers the following:

Example Messages for Health Care Providers

- Remind parents and caregivers that crying is normal for babies.

- Explain to parents that excessive crying is a normal phase of infant development.

- Share the “Crying Curve” information with parents: Infant crying begins to increase around 2 to 3 weeks of age, and peaks around 6 to 8 weeks of age; it then tapers off when the baby is 3 to 4 months old.

- Support parents and other caregivers of babies.

- During routine pediatric visits, be sure to ask parents how they are coping with parenthood and their feelings of stress.

- Assure them that it is normal to feel frustrated at long bouts of crying and a sudden decrease in sleep, but that things will get better.

- Give parents the number to a local helpline or other resource for help.

- Talk with them about the steps they can take when feeling frustrated with a crying baby, such as putting the baby safely in a crib on his or her back, making sure that he or she is safe, walking away and calling for help or a friend, while checking on the baby every 5 to 10 minutes.

- Let parents know what to check for when their baby is crying: signs of illness, fever or other behavior that is unusual, or discomfort like a dirty diaper, diaper rash, teething, or tight clothing, or whether he or she is hungry or needs to be burped.

|

Protective Factors for Child Abuse and Maltreatment

Child abuse prevention programs have long focused on reducing particular risk factors. However, increasingly, prevention services are also recognizing the importance of promoting protective factors: conditions in families and communities that research has shown to increase the health and well-being of children and families. These factors help parents who might otherwise be at risk of abusing or neglecting their children to find resources, supports, or coping strategies that allow them to parent effectively, even under stress (CWIG, 2008).

Parental/Family Protective Factors

Resilience is a concept that has been identified as an important protective factor among children who have been abused or maltreated. Research has identified that resilience was found to be related to personal characteristics of the child that can be protective against child abuse and maltreatment. Resilience is also a protective factor for parents. Parents who are emotionally resilient have a positive attitude, creatively problem solve, effectively address challenges, and are less likely to direct anger and frustration at their children (CWIG, 2008). These parents have:

- Secure attachment with children; positive and warm parent-child relationship

- Supportive family environment

- Come to terms with own history of abuse

- Household rules/structure; parental monitoring of child

- Extended family support and involvement, including caregiving help

- Stable relationship with parents

- A model of competence and good coping skills

- Family expectations of pro-social behavior

- High parental education

Community Protective Factors

- Mid to high socioeconomic status

- Access to health care and social services

- Consistent parental employment

- Adequate housing

- Family religious faith participation

- Good schools

- Supportive adults outside of family who serve as role models/mentors to child

Societal Protective Factors

- Families with two married parents encounter more stable home environments, fewer years in poverty, and diminished material hardship

- Supportive institutions in the society such as good child care and healthcare

Continue on to Conclusion |

|